People often like to show me their organisation’s performance reports, with lists of measures,data points, pie charts and actions. And then ask me what I think. Call it an occupation hazard.

Often the reports will have groupings around the departments, teams, or functions and it’s a way of tracking what the groups of people are doing (rather than achieving). Many of the performance measures are lists of ‘counts’. We did this many ‘things’ last reporting period; processed this many new business applications; this many customer phone calls came in; we did this many inspections; attended this many stakeholder engagement meetings…etc.

Performance measures in Reports are often like this, often because.

- The data for ‘counts’ is readily available and,

- Because most of the time the Reports are not about performance, but about demonstrating that we are busy and are doing our job. Why, often because the people reviewing the Reports are judging the people, “are they working hard enough?”

The only job of a performance measure

In the main, these ‘counts’ are not doing their job as a performance measure. The only job a performance measure has, is – to give us feedback on a performance result. Are we making progress towards that performance result, or not. Measures need to provide objective evidence about the result we are trying to make progress towards.

Some count measures can do this job.

- ‘The number of injuries each week’, for example can provide some feedback on the performance result “Our workplace is safe for our people”.

- ‘The number of promoters (advocates) we have in our customer portfolio’, can be a reasonable measure for the result: “Our customers are advocates of what we do”.

But even these counts only tell part of the story about progress towards that result. We almost always need more than one measure for each result.

An example

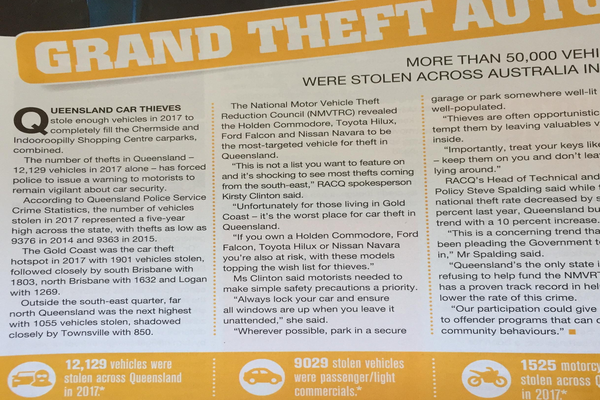

An article in a 2018 edition of the Road Ahead magazine, published by the RACQ the motoring association in the state of Queensland, written by Nathan Torpey. I am not criticising the article, or the author (who I made contact with prior to making this post). This is only an observation about how counts can mislead us.

The article describes the number of car thefts across the state of Queensland and identifies the Gold Coast as the “hotspot” based on the number of vehicles stolen.

Looking at the counts of things can often lead us to the wrong conclusions.

The information available to the public on the Transport and Main Roads website provides the ‘vehicles on register’, the number of vehicles registered throughout the state, by region and city.

Comparing the number of car registrations by city and the count of stolen vehicles in the article, we find that: the Gold Coast has a rate of car theft of 0.32%; Logan at 0.38% and Townsville City at 0.43%.

The is exactly in the reverse order of the “counts”.

Whilst the Gold Coast was identified as the hotspot for Queensland vehicle theft, the rate of theft of registered vehicles in Townsville as actually higher. Logan next, then the Gold Coast. The reverse order of the count, or number of vehicles stolen in those areas.

Conclusion

I often see this same problem in organisational performance measurement. Counts of things often do not make good performance measures. They can be useful, but we really need to know how these measures willprovide feedback on an outcome tha is important for us. By the way, this is Step 3 in the PuMP, performance measurement process. How to design and select meaningful performance measures.

Data is not measurement. Measurement uses data to perform the calculations.

We need this to inform us of how we are performing. The impact of our work on our outcomes. Feedback on the results we are seeking to progress towards.

Read more about getting better performance measures and KPIs in these blog posts.

Measuring Outcomes in Government

The Eight Steps to a High Performance Organisation

Or more information on this page.

Photo Credit:

Featured Image by William Iven on Unsplash